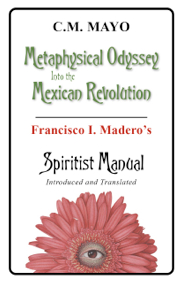

"In

a blend of personal essay and a rendition of deeply researched

metaphysical and Mexican history that reads like a novel, Mayo

provides

a rich introduction and the first English translation of what is

undoubtedly

one of the strangest, most thought-provoking, and utterly fascinating

books ever written in Mexico."

When Halley's Comet, that star

with a quetzal's tail, appeared in Mexican skies in 1910, it

heralded not only the centennial of Independence, but a deeply

transformative episode, the

Revolution launched by Francisco

I. Madero on November 20, what Javier Garciadiego calls "the

true beginning of a process, the birth of the modern Mexican

State."

The great chorus of historians

of Mexico agrees. Yet the deeply held spiritual beliefs that

prompted Madero, a kind-hearted Coahuilan businessman, onto the

battlefield are little known and when discussed at all, it is

more often as titillating gossip than with any attempt at understanding.

What were those beliefs? Some, such as the ideas from the Hermetica,

go back beyond the Renaissance into blurriest antiquity, but

in the main, it was Spiritism, the French offshoot of American

Spiritualism, fused with other late 19th century Anglo-American

and European metaphysics and psychical research, a touch of occult

Freemasonry, and the wisdom imparted by Lord Krishna in the Baghavad-Gita,

an ancient Hindu poem that also enthralled Madame Blavatsky,

Henry David Thoreau, José Vasconcelos, and the leader

of India's Independence movement, Mohandas Gandhi.

In fact, Madero stated his beliefs clearly and in detail in his

Manual espírita, which, astonishingly, he managed

to write in 1910. When he published it in early 1911 as "Bhima,"

and later that year, once elected President of Republic, attempted

to promote it from behind the scenes,

it earned him more enemies

than converts, for it was at sharp odds with the teachings of

the Catholic Church, on the one hand, and on the other, the Positivism

of the so-called científicos, the intellectual elite who

denied the relevance or even existence of supernatural phenomena.

Indeed, his book may have contributed to the visceral contempt

of those behind the overthrow of his government and his murder.

When C.M.

Mayo, a noted novelist, essayist and literary translator

encountered the Manual espírita in his archive

in Mexico's Ministry Finance, she recognized at once that it

was a vital document for understanding Madero and, therefore,

the Revolution itself. As a lark, she offered to translate it

into English, but as she herself admits, "not three pages

in, I was dumbfounded. I had no context for it."

But rather abandon the proyect, she began trying to find that

context, a rollicking odyssey of several years-worth of reading

and "armchair" travel, from the Burned-Over District

of New York to Paris, Barcelona, Brazil, and of course, Mexico,

where she consulted the remains of Madero's personal library—

perhaps one of the finest collections of 19th century esoterica

in Latin America— and as far as examining photos of Australia,

his guayule ranch in the desert where the spirits, so they said,

found it much easier to communicate with Madero.He was a writing

medium.

Whatever one's personal beliefs may be, it would be both unfair

and intellectually naïve to discard Madero's Spiritism as

"mere superstition." His Manual espírita,

published at the behest of the Second Mexican Spiritist Congress

of 1908, is, unabashedly, a religious manifesto and, as such,

has its place alongside the literature of other religions that

emerged at the same time, among them, Christian Science and Mormonism.

In a blend of personal essay and a rendition of deeply researched

metaphysical and Mexican history that reads like a novel, Mayo

provides a rich introduction to what is undoubtedly one of the

strangest, most thought-provoking, and utterly fascinating books

ever written in Mexico.