|

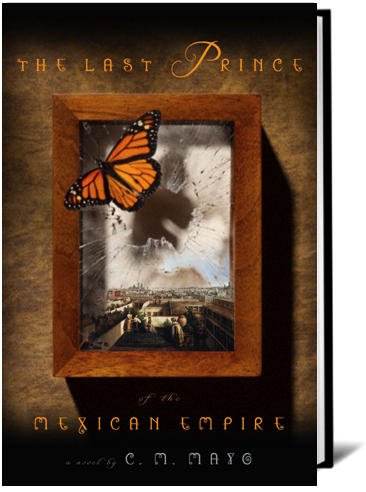

The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire A novel based on the true story |

|

|

HOME + C.M. MAYO + REVIEWS + EXCERPTS + Q & A + LISTEN + RESEARCH + EVENTS + ORDER +

HOME + C.M. MAYO + REVIEWS + EXCERPTS + Q & A + LISTEN + RESEARCH + EVENTS + ORDER + From the opening chapter, "The Darling

of Rosedale" ONCE

UPON A TIME there

was a little girl named Alice Green who lived on what people

who don't know any better would call a farm, but which her family

called their country estate. Rosedale's

main house was not especially fine, a clapboard box with a center

hall and, upstairs, a warren of bedrooms (one of the smallest

of which Alice shared with two sisters); however, it had fireplaces

in every room, a gleaming piano in the parlor, and Hepplewhite-style

chairs in the dining room. It was said that Pierre L'Enfant,

who had laid out the plan of the city of Washington, had advised

with the landscaping. There were avenues of dogwood and ornamental

hedges; peach, pear, cherry, fig, and apple orchards, grape arbors,

strawberry bushes, vegetable patches, including sensationally

prolific asparagus beds. ("O Moses," Alice's mother,

Mrs Green, would lament each spring with scarcely disguised pride.

"What am I to do with all this asparagus?") One might

also mention their chickens, ducks, geese, prize hogs and, feeding

on the hilly pastures that, here and there, dropped down to the

wooded canyon of Rock Creek, a herd of scrupulously tended milk

cows. As was common in those days, the family owned slaves; these

had their dowdy little cabins out back behind the stables, so

as not to ruin the pleasing view from the main driveway. Rosedale

crowned the heights above Georgetown, the then nearly century-old

tobacco port town that had been drawn into the western corner

of the District of Columbia. From the dormer window of her bedroom,

Alice could see hills undulating down for the few miles yonder

to the one they called "Rome" where the national capitol

sat: then no more than a tooth of a building. To the south, below,

lay the Potomac, with its jerry-built wharves and, shooting out

from the foot of the Francis Scott Key house, the rickety-looking

Aqueduct Bridge. On the opposite shore, in the blue distance:

the chip that was Arlington House, with its back to the fields

and forests of Virginia. Alas, oftentimes this vista was sullied

by smoke from one of Georgetown's paper mills or bone factories. ONCE

UPON A TIME there

was a little girl named Alice Green who lived on what people

who don't know any better would call a farm, but which her family

called their country estate. Rosedale's

main house was not especially fine, a clapboard box with a center

hall and, upstairs, a warren of bedrooms (one of the smallest

of which Alice shared with two sisters); however, it had fireplaces

in every room, a gleaming piano in the parlor, and Hepplewhite-style

chairs in the dining room. It was said that Pierre L'Enfant,

who had laid out the plan of the city of Washington, had advised

with the landscaping. There were avenues of dogwood and ornamental

hedges; peach, pear, cherry, fig, and apple orchards, grape arbors,

strawberry bushes, vegetable patches, including sensationally

prolific asparagus beds. ("O Moses," Alice's mother,

Mrs Green, would lament each spring with scarcely disguised pride.

"What am I to do with all this asparagus?") One might

also mention their chickens, ducks, geese, prize hogs and, feeding

on the hilly pastures that, here and there, dropped down to the

wooded canyon of Rock Creek, a herd of scrupulously tended milk

cows. As was common in those days, the family owned slaves; these

had their dowdy little cabins out back behind the stables, so

as not to ruin the pleasing view from the main driveway. Rosedale

crowned the heights above Georgetown, the then nearly century-old

tobacco port town that had been drawn into the western corner

of the District of Columbia. From the dormer window of her bedroom,

Alice could see hills undulating down for the few miles yonder

to the one they called "Rome" where the national capitol

sat: then no more than a tooth of a building. To the south, below,

lay the Potomac, with its jerry-built wharves and, shooting out

from the foot of the Francis Scott Key house, the rickety-looking

Aqueduct Bridge. On the opposite shore, in the blue distance:

the chip that was Arlington House, with its back to the fields

and forests of Virginia. Alas, oftentimes this vista was sullied

by smoke from one of Georgetown's paper mills or bone factories.Rosedale had been founded by Alice's maternal grandfather, General Uriah Forrest, who had served with General Washington and, famously, lost a leg in the Battle of Brandywine. Her maternal grandmother was a Plater who had grown up at Sotterley, one of the grandest of the Maryland Tidewater tobacco plantations. But so much had been lost by the time Alice was born: decades earlier, General Forrest had been bankrupted; as for Sotterley, the story was it had slipped from a great uncle's fingers in a game of dice. Alice's father worked in an office in the city of Washington, but when he was a young man, he had seen action in Tripoli with Commodore Decatur. Her father's uniform was in his seaman's trunk, an impossible-to-lift wooden box with handles made of rope. Alice and her brothers and sisters were allowed to take turns trying on the hat, which had an enormous plume, and posing in front of the mirror. They could take out the rusty musket and the saber, too (but they had to keep that in its sheath). There were a pair of high boots with cracked soles, once snow-white but now yellowed breeches, and a coat that smelled strongly of camphor but was nonetheless riddled with moth holes. When she was seven years old, Alice knew: she loved uniforms. She wanted, with all her heart, to go to Tripoli. "Girls can't wear uniforms," her older brother George said. "Silly," an older sister said, rolling her eyes. "Saphead," another brother, Oseola, said, and he stuck out his tongue. Thus was Alice persuaded to abandon her first ambition— but never the yearning for her destiny, which she felt as a blind girl might, laying a hand upon an elephant's side: this huge, warm, breathing thing. She had no notion of what it might be, no word to describe it, only the dim but solid knowledge that it was altogether different and inconceivably grander than the others's. She, being the youngest of eight, had always felt small but very special, and so this did not disconcert her. She took it as a given, as the color of the parlor's sofa was a given, that while whites went in that parlor, Negroes, except to dust and polish and serve tea, did not. What was to ponder in the fact that winter was bitter, summer steamy and buggy? Whether it were clear or cloudy, the sun rose every day, and that included Sunday, which was the day Mr and Mrs Green and all the little Greens crammed themselves into the big carriage and drove down toward the Potomac and, to save their mortal souls, sat through mass (no talking, no pinching) at Georgetown's Holy Trinity. And then came finishing school. At the Georgetown Female Seminary, in addition to French, music, and drawing, the history of Rome and such, Alice studied geography. She was diligent and she had a knife-sharp memory. Shown the Sandwich Islands once, she could pick them out of the Pacific cold. In the parlor, her father had a gold-edged Atlas of the World. She would sometimes lie on her stomach on the carpet, and propped on her elbows, study, say, Australia. Chile. Iceland. North Africa. She loved to trace her finger along the ragged curve of the Barbary Coast until it landed on Tripoli. Tripoli. Alice whispered the names of the Arab cities: Tangiers. Algiers. Tunis. Cairo. She would close her eyes and imagine the musky scents of their bazaars, the tables piled with bangles and silks, oranges sweet as the sun. Her father had explored ancient temples, ridden a real camel, and held in his own hands a 2,000 year-old kylix painted with the figure of the Minotaur. He had seen Malta, Mallorca, Gibraltar. On the map, Alice would touch each of these magical places, and then slide her pinky over the aqua-blue swath of paper that was the Atlantic. And then her finger would arrive at Chesapeake Bay, sliding up the sinuous Potomac to... Oh, Dullsvania. Blahsberg! Boringopolis!! She knew there was another life waiting for her, a life that would be as romantic as anything out of The Thousand and One Nights. Here, in the country, it sometimes seemed that she had nothing to do but sit at the window, her chin in her hands, and watch crows alight on the fence-rails. (Her mammy said that in the night the crows flew to Mexico, to feed on the dead soldiers. In the day, they digested the flesh. But Alice knew better than to pay heed to Negro talk.) Sometimes, early in the mornings before school, her mother would make her help feed the chickens, and inspect the dairy. Was that not the rudest thing in the world? One day, she would wing across an ocean. She would be adored; like Commodore Decatur, she would be remembered for a hundred years. No: more than a hundred years. |

|

|

|