|

Author of The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire, etc. |

|

|

Book Review

by C.M. Mayo Book Review

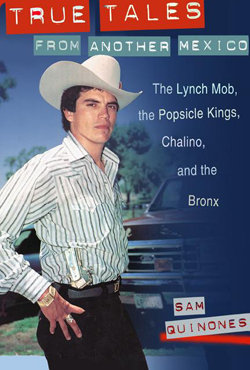

by C.M. Mayo TRUE TALES FROM ANOTHER MEXICO: TRUE TALES FROM ANOTHER MEXICO:The Lynch Mob, The Popsicle Kings, Chalino and the Bronx by Sam Quinones University of New Mexico Press, 2001 Review originally published in The Wilson Quarterly, winter 2001 "Poor Mexico," lamented the dictator Porfirio Díaz, "so far from God and so close to the United States." Most Americans writing on their neighboring country fall deep into this well-worn groove of portraying a Mexico that is to be pitied. And so True Tales from Another Mexico is a wonder and a delight. In this beautifully written collection of essays, Sam Quinones tells the stories of Mexicans as diverse as Queen Abenamar I, a Mazatlán red-light district transvestite and beauty queen, and Zeus García, bus boy by day, "high priest" of Zapoteco basketball by night and weekend. The book opens with the story of Chalino Sánchez, the smoldering-eyed Sinoloan who created a new genre of popular music, the corrido prohibido, or narco ballad. In the late 1980s, having done time in a Tijuana prison, Chalino was in LA washing cars when he began to write his ballads, singing them with his own bark of a voice, and selling the cassettes at car washes and swap-meets all over LA. Soon, though no radio DJ would play them, Chalino's "rough sound ignited immigrant LA". Today the royalties are worth millions. Millions of dollars also crossed hands when Televisa, Mexico's entertainment conglomerate, sold its soap opera called Los Ricos También Lloran, (The Rich Also Cry) to, among other countries, Spain, Italy, Yugoslavia, and Russia. Los Ricos was such a success that when its star, Verónica Castro, arrived at the Moscow airport, it had to be closed because of the thongs who had come to greet her. Her presence at the Bolshoi Ballet caused a stampede; her hotel room, at that time of Russia's severe economic crisis, was filled with flowers from her fans, who, when they saw her on the street would often burst into tears. "Wherever I'd go," the bewildered Castro told Quinones. Equally remarkable are "The Popsicle Kings of Tocumbo" whose thousands of "La Michoacana" ice-cream shops dot the republic from Tijuana down to Tapachula, hard by the border with Guatemala. Owned by various families, friends and neighbors, these little shops have proved so prosperous that the entrepreneurs' tiny home town of Tocumbo, Michoacán is filled with lavish houses, forests of satellite dishes, a beautiful park with a swimming pool, a church designed by a world-class architect, and a giant statute— "big as a three story house"— of an ice-cream cone. Not that all of the stories end happily. Chalino Sánchez, for example, was kidnaped and shot in the back of the head. "Lynching in Huehutla" was so gruesome I found it difficult to read; another, "The Dead Women of Juárez," reports on the hundreds of murders of young women in that hardscrabble border town, most of which remain unsolved. Quinones also takes an unblinking look at glue-sniffing gang wannabes, and Nuevo Jerusalén, a cult-run town he had to visit three times before he would be admitted— on the day the adults were all dressed as saints, their halos made of wire hangers and tin-foil. These "true tales" are indeed of "another Mexico," mind-boggling in its complexity. Intimately tied to the US, it is at times and in places "far from God," but, as Quinones ends this splendid book, well on its way to being "robust and part of the world." |