|

Book Review

by C.M. Mayo Book Review

by C.M. Mayo

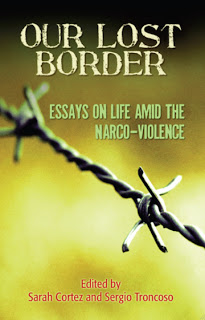

OUR LOST BORDER OUR LOST BORDER

Edited by Sarah Cortez and Sergio Troncoso

Arte

Público Press, Houston, Texas

Trade paperback $19.95, March 30, 2013

ISBN: 978-1-55885-752-0

Review originally published in Literal,

2013

Lurid television, newspaper stories, and

cliché-ridden movies about

Mexico abound in English; rare is any writing that plumbs to

meaningful depths or attempts to explore its complexities. And

so, out of a concatenation of ignorance, presumption and prejudice,

those North Americans who read only English have been deprived

of the stories that would help them see the Spanish-speaking

peoples and cultures right next door, and even within the United

States itself, and the tragedies daily unfolding because of or,

at the very least kindled by, the voracious North American appetite

for drugs. For this reason, Our

Lost Border: Essays on Life Amid the Narco-Violence,

a treasure trove of one dozen personal essays, deserves to be

celebrated, read, and discussed in every community in North America.

Not a book about Mexico or narcotrafficking per se, Our Lost

Border is meant, in the words of its editors, Chicano writers

Sarah Cortez and Sergio

Troncoso, "to bear witness," to share what it has

been like to live and travel in this region of Mexico's many

regions, and what has been lost.

Snaking from the Pacific to the Gulf of Mexico, the 2,000 mile-long

U.S,-Mexico border is more than a fence or river or line on a

map of arid wastelands; it is the home of a third culture or,

rather, conglomeration of unique and hybrid cultures that are,

in the words of the editors, "a living experience, at once

both vital and energizing, sometimes full of thorny contradictions,

sometimes replete with grace-filled opportunities."

In "A World Between Two Worlds," Troncoso asks, "what

if in your lifetime you witness a culture and a way of life that

has been lost?" And with finesse of the accomplished novelist

that he is, Troncoso shows us how it was in his childhood, crossing

easily from El Paso to Ciudad Juárez: family suppers at

Ciros Taquería near the cathedral; visits to his godmother,

Doña Romita, who had a stall in the mercado and who gave

him an onyx chess set; getting his hair cut by "Nati"

at Los Hermanos Mesa… Then, suddenly, came the carjackings,

kidnappings, shootings, extorsions. For Troncoso, as for so many

others fronterizos, the loss can be measured not only in numbers—

homicides, restaurants closed, houses abandoned— but also

in the painful pinching off of opportunities to segue from one

culture and language with such ease, as when he was a child,

for that had opened up his sense of possibility, creativity,

and clear-sightedness, allowed him develop a practical fluidity,

what he calls a "border mentality"— not to judge

people, not to accept the presumptions of the hinterlands, whether

of the U.S. or Mexico, but "to find out for yourself what

would work and what would not."

For many years along the border, and in some parts of the interior,

drug violence was a long-festering problem. It began to veer

out of control in the mid-1990s; by the mid-2000s it had become

acute, metastasising beyond the drug trade itself into kidnapping,

extorsion and other crimes. Short on money and training- in part

a result of a series of fiscal crises beginning in the early

1970s— the police had proven ineffective, easily outgunned

or bribed. Shortly after he took office in late 2006, President

Felipe Calderón unleashed the armed forces in an all-out

war against the cartels and that was when the violence along

the border erupted as the narco gangs fought pitched battles

not only against the army, marines, and federal and local police,

but also and especially, and in grotesquely gory incidents, each

other.

Some of the worst fighting concentrated in the border state of

Tamaulipas in its major city, Tampico, which is a several hours'

drive south of the border with Texas, but a major port for cocaine

transhipments.

In the opening essay, "The Widest of Borders," Mexican

writer Liliana V. Blum provides a Who's Who of the narco-gangs,

from the Gulf Cartel, which got its start with liquor smuggling

during Prohibition, to its off-shoot, the Zetas, which formed

around a nucleus of Mexican Army special forces deserters in

1999, then joined the Beltrán Leyva Brothers, blood enemies

of the Sinaloa Cartel. Fine a writer as she is, Blum's experiences,

which included having to drive her car through the sticky blood

of a mass murder scene on the way home from her daughter's school,

make discouraging reading.

In "Selling Tita's House," Texas writer Mari Cristina

Cigarroa recounts her family's visits and Christmases to her

grandparents' elegant and beloved mansion in Nuevo Laredo. But

then, with soldiers in fatigues patrolling the streets, Nuevo

Laredo seemed "more like an occupied city during a war."

Chillingly, she writes, "I awoke to the reality that cartels

controlled Nuevo Laredo the day I could no longer visit the family's

ranch on the outskirts of the city."

The strongest and most shocking essay is journalist Diego Osorno's

"The Battle for Ciudad Mier," about a town shattered

in the war between the Zetas and the Gulf Cartel for Tampaulipas.

I have hope for Mexico for, as as an American citizen who has

lived in Mexico's capital and traveled and written about its

astonishingly varied history, literature, and varied regions

for over two decades, I know its greatness, its achievements,

its resilience, and creativity. But in his foreword, Rolando

Hinojosa-Smith rightly chides, "The United States needs

to wake up."

|