|

In 1999, C.M. Mayo founded Tameme, the annual bilingual

journal of new writing from North America, Canada, the U.S.,

and Mexico. One of the journal’s goals, she explains, is

to serve as a way to make people aware of the art of English

to Spanish literary translation, "of the painstaking effort

to get every word just right, of finding the elegance, the rhythm,

and the charm, if you will, of the original." In bringing artists of

the Americas together under one cover, Mayo hopes readers and

writers alike will use Tameme as a cultural, as well as

literary, forum. The following outlines her efforts to make this

vision a reality. In 1999, C.M. Mayo founded Tameme, the annual bilingual

journal of new writing from North America, Canada, the U.S.,

and Mexico. One of the journal’s goals, she explains, is

to serve as a way to make people aware of the art of English

to Spanish literary translation, "of the painstaking effort

to get every word just right, of finding the elegance, the rhythm,

and the charm, if you will, of the original." In bringing artists of

the Americas together under one cover, Mayo hopes readers and

writers alike will use Tameme as a cultural, as well as

literary, forum. The following outlines her efforts to make this

vision a reality.

When— and why—did

you first get the idea to publish a bilingual literary magazine

of translations?

It was after

the North American Free Trade Act (NAFTA) had been passed, when

I was living in Mexico City and beginning to look around at what

was being translated, both from English-into-Spanish and Spanish-into-English.

I knew there was a lot of amazing work out there, and I was quite

surprised to find how little of it was being translated. I was

also surprised by the conservatism of many translators - picking

the tried-and-true over newer, and perhaps riskier, writers.

For example, I was seeing translations of the short stories of

Ernest Hemingway and Eudora Welty, but none of, say, A. Manette

Ansay or Sherman Alexie, two of the writers I think are among

the best of their generation. This isn’t necessarily a criticism.

After all, a wonderful writer is wonderful to translate, whether

they’ve been dead for 500 years or whether they happen to

be living and breathing next door. Nonetheless, I wanted to encourage

more translations of the many superb but relatively less-known

contemporary English- and Spanish-language writers.

What are

your goals for Tameme?

One goal for

Tameme is to bring out literary translations and to let

the magazine serve as a forum for the art of translation. Thus,

Tameme includes biographies of the translators and extensive

translators’ notes. There is a space reserved at the back

where translators may write about whatever they want, from the

specific technical issues that came up in the translation, to

their general philosophy of translation, or even just anecdotes

about how they happened to begin translating.

Championing quality

translation is so important. There is such an ocean of ignorance.

I’ve had many people tell me, "Oh, why don’t you

save money and instead of hiring a translator, just run the story

through a computer program?" It curls my toes!

Another goal

is to put the writers and readers of North America together.

By "North America," I mean anyone who is from and/or

lives in Canada, the U.S., or Mexico. Whatever one may think

of NAFTA, the fact is that economic and financial ties among

Canada, the U.S., and Mexico are becoming stronger. It’s

a wonderful thing to get to know more about each other’s

cultures and languages. I like to think of, say, a Canadian reader

coming across Margaret Atwood in the same issue of Tameme

as Alberto Blanco, a Mexican poet he might not have heard

of before. Or, similarly, perhaps a Mexican reader might find

Edwidge Danticat or Charles Simic next to a favorite, such as

Juan Villoro or Coral Bracho.

How did you

choose the name, Tameme, and what is its significance?

Tameme (pronounced "ta-meh-meh")

is a Nahuatl (Aztec) word meaning "messenger" or "porter."

Who is your

target audience?

Anyone who enjoys

reading literature, and also English to Spanish and Spanish to

English translators. Translators have been the biggest supporters

of Tameme, both as contributors and as readers. Nonetheless,

because Tameme publishes the translations side-by-side

with the originals, it can be read by someone who only reads

Spanish as well as by someone who only reads English.

How did

you go about turning a dream into reality (recruiting contributors,

advertisers, etc.)? Do you have some good anecdotes?

Roger Mansell,

my dad, who has more than 25 years of experience in the printing

and graphics business, was a big help from the beginning. He

gave Tameme space in his office in Los Altos, California,

and also helped set up Tameme, Inc. as a California-based nonprofit,

which was a very sticky wicket of paperwork!

For the first

issue, I asked for work from writers and translators I knew,

as well as from members of the editorial advisory board. I also

just straight out asked for the work I wanted. That was the case

with Margaret Atwood. I found her essay "The Grunge Look"

in a PEN Canadian anthology, and wrote to her care of the publisher.

She wrote back very kindly granting us permission, and we went

ahead and commissioned the translation. That essay is in our

first issue.

For the second

issue, we cast the net very wide with calls for submissions in

Poets & Writers, the Writers Carousel, and

all over the Internet. We also sent flyers to around 200 universities.

Some of the pieces we received were complete surprises, such

as Silvia Tandeciarz’s translations of the poetry of Juana

Goergen.

I also attended

the American

Literary Translators Association (ALTA) conferences and queried several of the

Spanish-language translators. It was at an ALTA conference that

I met Cola Franzen, Claire Joysmith, Elizabeth Gamble Miller,

and Mark Schafer for the first time. Right there, four amazing

translators!

As for advertisers,

most of our ads are "exchanges." That is, we provide

a free ad to other literary journals and, in turn, they each

give Tameme a free ad. It’s an efficient way for

a nonprofit "litmag" to get the advertising that our

budget would not otherwise permit. I also hope our readers benefit

from learning about other journals and translation programs.

When did your

first issue come out?

1999. As I mentioned

before, this is the one that contained Margaret Atwood’s

"The Grunge Look," a hilarious account of her travels

in 1960s Europe and how she was always being mistaken for an

American. In addition, there was an essay by Mexican Juan Villoro

about his eccentric grandmother, and stories by A. Manette Ansay

and Edwidge Danticat, and Mexicans Fabio Morabito and Daniel

Sada.

What was the

reaction to this first issue?

The reaction

was, on the one hand, indifference, and on the other, this amazing

sort of jump-up-and-down enthusiasm. The indifference mostly

came from people who seemed to think that if they don’t

read Spanish or have any interest in learning Spanish, it’s

not for them. The enthusiasm came from people who love Spanish,

have lived in Mexico or Central or South America, and from many

people who write in Spanish. They were genuinely excited to see

Spanish-language work getting a broader diffusion. Many people

wrote us heartfelt letters. I even had a few phone calls from

people I didn’t know, just to tell us how much they liked

it. So that was really a thrill. We got a very generous review

in The Bloomsbury Review and another, for the second issue

of Tameme, in the Literary Magazine Review. Several

other literary journal editors (including Jack Grapes of ONTHEBUS

and Howard Junker of Zyzzyva) sent blurbs. Best of all,

the Fund for U.S.-Mexico Culture gave Tameme a generous

grant to do the second and third issues.

What was the

theme of the second issue?

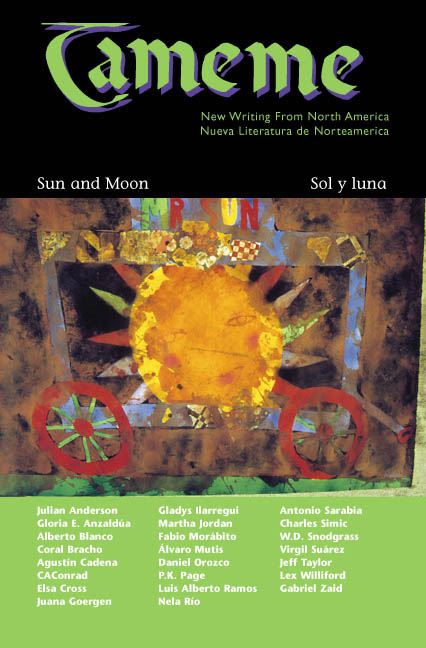

I ssue #2 was entitled

"Sun and Moon/Sol y Luna." It featured poems by W.D. Snodgrass,

"The Capture of Mr. Sun" and "The Capture of Mr.

Moon," together with their illustrations as the cover art,

two gorgeous collage-like paintings of the same titles by DeLoss

McGraw. The title for the issue, "Sun and Moon," came

naturally after the material had been assembled. This issue opens

with a very strange and darkly funny essay by Jeff Taylor about

working in a meat packing plant. It also includes stories by

Lex Williford (winner of the Iowa Prize), Luis Arturo Ramos (one

of Mexico’s most outstanding writers), and includes poems

by Alberto Blanco, Alvaro Mutis, P.K. Page, Gabriel Zaid, and

many others. ssue #2 was entitled

"Sun and Moon/Sol y Luna." It featured poems by W.D. Snodgrass,

"The Capture of Mr. Sun" and "The Capture of Mr.

Moon," together with their illustrations as the cover art,

two gorgeous collage-like paintings of the same titles by DeLoss

McGraw. The title for the issue, "Sun and Moon," came

naturally after the material had been assembled. This issue opens

with a very strange and darkly funny essay by Jeff Taylor about

working in a meat packing plant. It also includes stories by

Lex Williford (winner of the Iowa Prize), Luis Arturo Ramos (one

of Mexico’s most outstanding writers), and includes poems

by Alberto Blanco, Alvaro Mutis, P.K. Page, Gabriel Zaid, and

many others.

As you published

additional issues, what were some "lessons learned"

from the process?

Getting the text

in Spanish to line up with the English side-by-side was much

trickier than it looked at first. We had lines jumping and accents

that wouldn’t print. Formatting that first issue was a nightmare.

With all the snafus, it took us almost six months. Finally, our

designer (bless her heart!) got the template down clean. For

the second issue, I learned how to use Pagemaker so I could do

it myself.

Who helps

provide assistance during the editing process?

We have a couple

of readers who help with the unsolicted material, and also an

editorial advisory board of writers, translators, and readers

who often make suggestions and send work. Once the issue has

been assembled, I do very little editing; basically copyediting.

For the Spanish-language copyediting, I rely on Bertha Ruiz de

la Concha, a really splendid Mexican translator and editor.

Tell us about

the third issue.

The third issue,

"Reconquest/Reconquista," has been made possible by the grant

from the Fund for U.S.-Mexico Culture, and I am really excited

about it. The theme of "reconquest" runs throughout

the issue, and is widely interpreted. For instance, we will feature

a poem by Juana Goergen, "Reconquista," and an elegant

and very thoughtful essay by Philip Garrison, "The Reconquista

of the Inland Empire." One poem, "Arlington House,"

by Washington, DC-area poet M.A. Schaffner, is about the mansion

of Robert E. Lee that now sits in the middle of Arlington Cemetery

surrounded by the graves of Union dead. The issue also includes

work by Colette Inez, Alberto Blanco, and Eduardo Gonzalez-Viana,

a wonderful novelist and short story writer from Peru who lives

in Oregon. He is definitely a writer to watch. We’ve also

got a beautiful short story by José Skinner, who, by the

way, is an accomplished Spanish translator himself. The third issue,

"Reconquest/Reconquista," has been made possible by the grant

from the Fund for U.S.-Mexico Culture, and I am really excited

about it. The theme of "reconquest" runs throughout

the issue, and is widely interpreted. For instance, we will feature

a poem by Juana Goergen, "Reconquista," and an elegant

and very thoughtful essay by Philip Garrison, "The Reconquista

of the Inland Empire." One poem, "Arlington House,"

by Washington, DC-area poet M.A. Schaffner, is about the mansion

of Robert E. Lee that now sits in the middle of Arlington Cemetery

surrounded by the graves of Union dead. The issue also includes

work by Colette Inez, Alberto Blanco, and Eduardo Gonzalez-Viana,

a wonderful novelist and short story writer from Peru who lives

in Oregon. He is definitely a writer to watch. We’ve also

got a beautiful short story by José Skinner, who, by the

way, is an accomplished Spanish translator himself.

Please talk

about your own background and writing/translating experience.

I moved to Mexico

City in 1986 when I got married. I had never studied Spanish,

only French and German, so I went to the Monterey Institute in

Monterey, California, for an intensive four-week Spanish immersion

course. Once in Mexico City, I took more Spanish classes and

began working in an international investment bank. By 1988, I

was able to teach finance and economics in Spanish. My academic

background is in economics (B.A. and M.A., University of Chicago),

but ever since I was small I had always written stories. In 1990,

I began taking my literary writing seriously and signed up for

some summer writers conferences. By 1992, I was publishing stories

and poems and had begun to translate Mexican poetry.

As for my current

work, I have a book coming out this fall, Miraculous Air: Journey of a Thousand Miles Through

Baja California, the Other Mexico (University of Utah Press), and a book

of short stories, Sky Over El Nido (University of Georgia

Press), which won the Flannery O’Connor Award. I’ve

been publishing in literary journals, most recently essays in

Fourth Genre and Southwest Review, stories in Natural

Bridge and Turnrow, and poetry in West Branch.

Right now, I am working on a novel set in Mexico City.

In recent years,

my translating of Mexican poems has taken a back seat to editing

Tameme, though I do have some translations of poems by

Tedi Lopez Mills in the anthology edited by Monica de la Torre

and Michael Wiegers, Reversible Monuments (Copper Canyon,

2002).

What has been

the most "fun" aspect of publishing Tameme?

The fun part

is finding something I feel really thrilled about bringing to

a translator and to new readers. I’ve also enjoyed choosing

the cover art. I like to have something kind of strange, powerful,

and crazy-bright with colors. The translators’ notes, when

they come in, are always a treat to read.

What has been

the most challenging aspect?

The challenging

parts of editing Tameme are: 1) the paperwork (just crushing

at times), and 2) having to say "no" to so many of

the submissions we receive. It’s never easy to say "no,"

but, alas, there are only so many pages we can print. If we had

no monetary limitations, we could come out more frequently. As

it is, we can manage "once a year-ish."

Do you have

any suggestions about how to get literary translations published?

I really encourage

anyone who is interested in trying to publish some literary translations

to go ahead, try it! I think it’s easier to start with something

relatively small, say, a poem you really like. Have a go at it,

and then if you don’t have an address for the writer, simply

write to him or her care of the publisher. Ninety-nine times

out of a hundred, writers are thrilled to have a translator take

an interest in their work.A literary journal is the best place

to send a literary translation. But I think the first thing to

have clear is that literary journals, and I mean both the specialized

translation journals such as Tameme, Beacons, and Two

Lines, and the wide range of U.S. and Canadian literary journals

that also consider translations, are open to unsolicited work.

That means you don’t have to know the editor. Just check

out the submission guidelines and then send in your work.

It is crucial

to understand that "litmags" are nonprofit. None of

them, however fancy their covers may appear, make a profit. Few

have paid staff, and those few that do have very small staffs.

In short, for the editors, it’s a labor of love. (That also

means that your "payment" will most likely be two copies

of the journal. There are exceptions, but generally speaking,

literary translation for literary journals is not a way to make

money.) Thus, it is important to include a self-addressed, stamped

envelope for a reply, and to respect the editors’ time by

having your permissions all lined up before you start sending

translations out. A brief and business-like cover letter is fine.

It should include: 1) your name, address, telephone number, and

e-mail address; 2) the basic information of what you are offering;

3) a copy of a letter from the poet or writer granting permission

to publish the translations; and 4) a brief biographical note

about yourself. More than a page of information, I think, is

clutter. It also helps to keep in mind that literary journals

receive mountains of unsolicited work, so even excellent work

can receive a rejection slip. No need to get discouraged. It’s

just a question of being persistent and to keep sending, sending,

sending. One writer compared sending work out to throwing spaghetti

noodles against the wall; you never know which one will stick!

On my website

(www.cmmayo.com) I have a workshop page with an

essay containing more detail about submitting work to literary

journals. It

is meant for my writing students, but most of the advice also

applies to submitting translations. Publishing in a literary

journal can be very encouraging, both for the translator and

for the writer or poet. I can’t recommend it enough.

Where can

one find journals to submit literary translations?

One place to

start is in your local bookstore, though not all carry literary

journals, and even the best-stocked stores do not carry all of

the many wonderful journals that are out there. Public and university

libraries often have excellent collections. And, there are directories

of listings of journals with brief descriptions, addresses, and

so on in The Writers Market. On the web, a superb source

of information is the website of the Council of Literary Magazines

and Small Presses (www.clmp.org), which has links to

many of its members. Last June, I attended the New York City

Literary Magazine Festival where there were 105 "litmags"

represented. There is certainly no shortage of places to send

work! In fact, several editors told me they were very eager for

more submissions of translations.

You are wearing

two different hats simultaneously— litmag editor and creative

writer. Any advice for others?

Writers are often

interested in starting litmags because they want to publish their

own writing. I think that’s something to be very cautious

about, because when motives are mixed, the quality can get muddy.

It’s challenging to remain objective about one’s own

writing. How can one be objective about one’s own child?

So, for me, Tameme is about translating and editing, and

my own writing I send elsewhere. There are, of course, many cases

of editors including their own writing in their journal. I am

thinking of Harry Smith’s deliciously puckish essays that

he published in The Smith. The one rule of the literary

life is there are no rules.

You have a

home in both the U.S. and Mexico. What insights into the culture

of Mexico has the literature of that country given you?

Much of the literature

of Mexico comes out of Mexico City, which is not any more representative

of the country than, say, Manhattan is of the vast spaces between

Seattle and Miami. With that caveat, the literature has shown

me a Mexico that is the cliché of cacti and campesinos,

but also very cosmopolitan¾ interested in the Rolling

Stones and Bach, Madonna, Princess Di, and shopping trips to

Houston. At the same time, it is a country with a connection

to its past that extends to the remote provinces. So I would

have to say a sense of the overwhelming importance of Mexico

City. In terms of its cultural, financial and political importance,

it’s like a Washington DC, New York City and Los Angeles

rolled into one. On the other hand, not all of Mexico’s

literature is coming out of Mexico City, nor is it necessarily

in Spanish. Monica de la Torre and Michael Wieger’s new

anthology of Mexican poetry, Reversible Monuments, includes

poems in several indigenous languages— and their style and

content were, for me, something entirely new.

But what is the

definition of "the literature of the country?" I like

to think of it as including the writing of foreigners about Mexico.

There is Calderon de la Barca’s unparalleled Life

in Mexico,

Gooch’s Among the Mexicans, Crosby’s Last

of the Californios, Flandreau’s Viva Mexico,

and Steinbeck’s The Log from the Sea of Cortez.

More recently, a whole new Mexico was opened to me through

reading the American journalist San Quinones’ True Tales From Another Mexico. And

then there is Alma Guillermoprieto, a Mexican journalist who

writes in English for The New Yorker.

Currently, I’m reading Maximilian von Habsburg’s astonishingly

vivid and elegant Memories of My Life. He was an Austrian

archduke, but also the emperor of Mexico. One of the greatest

books ever written was the Spanish conquistador Bernal Diaz del

Casillo’s memoir The Conquest of Mexico. In short,

narrowing the definition gets complicated.

Do you have

a favorite Mexican writer?

There are so

many— Elena Poniatowska, Carlos Fuentes, Juan Villoro, Alberto

Blanco, Coral Bracho, Fabio Morabito…

What do you

wish your legacy will be as editor of Tameme?

I hope Tameme

will be remembered as having brought writers to new readers,

and having helped bring the message that literary translation

is an art, and that it matters very much how well it is done.

I would be thrilled if Tameme were remembered as having

come along in the footsteps of some of the earlier international

literary journals that featured translation, such as Botteghe

Oscure, El Corno Emplumado, and Mandorla. I was inspired

by their examples and I hope Tameme, in turn, will inspire

others to start international literary journals, and especially

journals that feature translation. |