|

An offshoot of American Spiritualism,

Spiritism was codified by French educator Hippolyte Léon

Denizard Rivail, aka Allan

Kardec, and his disciples in the second half of the nineteenth

century. Madero, scion of a wealthy family from Coahuila in northern

Mexico, was a student in France in 1891 when he encountered Kardec's

magazine and books.

According to Spiritism, because we are spirits it follows that

we can communicate with other spirits, embodied or not. Spiritism

is a religion but also the most modern of modern science, Kardec

argued; as a scientist might peer through a microscope to perceive

the detail in a leaf, so a scientist could employ a medium to

learn from the spirit world.

Both in France and on his return to Mexico, Madero met with a

circle of fellow Spiritists to develop his psychic abilities,

in particular, for receiving communications from the dead by

means of automatic writing. In 1907, a militant spirit named

"José" began to advise Madero on writing the

book that would serve as his political platform: La sucessión

presidencial en 1910 (The Presidential Succesion of 1910),

a work well-known to scholars of the 1910 Revolution. Then, so

we learn from Madero's mediumnistic notebook, José informed

Madero that he would write Manual espírita, a work

"which will cause an even greater impression."

By the time I began to leaf through Manual espírita

in Madero's archive nearly a century later, quite the opposite

seemed to have been its destiny.

It turns out that there are, albeit astonishingly few, Mexican

historians who have written in some depth and seriousness about

Madero's Spiritism: Manuel

Guerra de Luna, Enrique Krauze, Alejandro Rosas Robles, and

Yolia

Tortolero Cervantes. Although, at the time I happened upon

Manual espírita in the archive, it was nigh impossible

to buy a copy, Alejandro Rosas Robles had included it in his

10 volume compilation, Obras completas de Francisco Ignacio

Madero, published in 2000. I should also note the esteemed

Mexican novelist, Ignacio Solares, whose Madero, el otro

delved, and knowingly, into his esoteric philosophies.

All that said, in Mexico, where Madero has the stature of an

Abraham Lincoln, celebrated in every textbook of national history,

and the Revolution he proclaimed in his Plan de San Luis Potosí

commemorated every November 20th, Bhima's Manual espírita

lay murky leagues below the cultural radar, and the nature and

historical and philosophical context of its contents were terra

incognita to most historians of the Mexican Revolution. It had

never been translated.

I was a translator—and one keenly aware of how little Mexican

writing sees publication in English. And I knew enough to know

that, whatever its contents, the fact that Francisco I. Madero

had written this book gave it importance, for it would illuminate

the character and personal and political philosophies of the

leader of the 1910 Revolution. It bears repeating that Madero

took the trouble to write it in the same year he declared and

led that Revolution, and he published it in 1911, the year of

his nation-wide campaign that resulted in his election to the

presidency of the Republic. Whatever this book contained, it

must have been exceedingly important to him.

From the first page of my self-appointed task, however, my instinct

was to wince. Nervous laughter, eye-rolling... It was obvious

to me that most educated readers, including most historians of

Mexico, would regard Madero's Spiritist Manual with puckerlips

of disgust.

What had I taken on?

Madero was murdered in the coup d'etat of 1913. As I read deeper

into that terrible episode, I was flummoxed to learn from U.S.

Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson's memoir that, after arresting President

Madero, General Victoriano Huerta sent his first communication

to the U.S. Legation, asking the ambassador, should he lock Madero

in the lunatic asylum?

I soon realized that to merely translate this century-old book

would be a disservice not only to its author, but to myself and

to the reader—the latter, as were those archvillians of

1913, General Huerta and Ambassador Wilson, presumably as unlettered

as I was on the history of metaphysical religion and subjects

as various as the afterlife, angels, astral planes, automatic

writing, bilocation, and the teachings of Lord Krishna in the

Hindu wisdom book, the

Bhagavad-Gita.

What Spiritist Manual needed was a book-length introduction,

a framing context for English language readers who know little

or nothing of Madero, and/or of Mexican history, and, most crucially,

of the metaphysical philosophies Madero had embraced and espoused.

And so, beginning with Kardec, I began a marathon of reading.

There was much to glean from the works of the aforementioned

handful of Mexican historians; also, to my happy surprise, from

recent scholarly works about nineteenth and twentieth century

metaphysical religion, parapsychology, and occult traditions—

serious considerations of what many historians still dismiss,

as Dame Frances Yates, leading scholar of the esoteric traditions

of the Renaissance, archly dismissed nineteenth and twentieth

century Rosicrucians as "below the notice of the serious

historian." These works include Catherine Albanese's A

Republic of Mind & Spirit: A Cultural History of American

Metaphysical Religion (Yale University Press); Joscelyn

Godwin's The Theosophical Enlightenment (State University

of New York Press); John Warne Monroe's Laboratories of Faith:

Mesmerism, Spiritism and Occultism in Modern France (Cornell

University Press); Janet Oppenheim's The Other World: Spiritualism

and Psychical Research in England, 1850-1914 (Cambridge University

Press), and, neither last nor least, Jeffrey J. Kripal's Authors

of the Impossible: The Paranormal and the Sacred (University

of Chicago Press).

In addition, I combed through Madero's personal library, which

is preserved in the Centro de Estudios de Historia de México

in Mexico City. As I could now appreciate, Madero had assembled

a large and sophisticated collection of turn-of-the-last century

European and Anglo-American esoterica, including two English

translations and J. Roviralta Borrell's Spanish translation of

the Bhagavad-Gita, the latter heavily annotated in Madero's own

handwriting.

Thus:

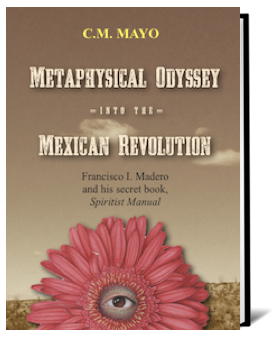

Metaphysical

Odyssey into the Mexican Revolution: Francisco I. Madero and

His Secret Book, Spiritist Manual. The odyssey I recount

is not only Madero's, but my own into that vast and vertiginous

view made possible by my having made, and inviting the reader

to make, the Kantian cut— although I did not use that term.

I cracked open the door to greater understanding, not by embracing,

nor by rejecting Madero's philosophies and assertions, but by

accepting—simply accepting— that what I understand

to be reality and what it actually is are not necessarily the

same thing because I, like any human being, with wondrous yet

rangebound senses and brain, cannot comprehend the fullness and

every last quarky detail of the cosmos. What we know is a nano-slice,

if that. Thus:

Metaphysical

Odyssey into the Mexican Revolution: Francisco I. Madero and

His Secret Book, Spiritist Manual. The odyssey I recount

is not only Madero's, but my own into that vast and vertiginous

view made possible by my having made, and inviting the reader

to make, the Kantian cut— although I did not use that term.

I cracked open the door to greater understanding, not by embracing,

nor by rejecting Madero's philosophies and assertions, but by

accepting—simply accepting— that what I understand

to be reality and what it actually is are not necessarily the

same thing because I, like any human being, with wondrous yet

rangebound senses and brain, cannot comprehend the fullness and

every last quarky detail of the cosmos. What we know is a nano-slice,

if that.

In other words, we don't have to accept nor reject Madero's ideas—yes,

we can keep the lid on our coconuts while seriously considering

a whole lot of super freaky stuff!

Although Madero's Spiritist Manual is radically different

in its content and tone from Strieber's Communion, like

that mystical text, if encountered with historical and philosophical

context and with the power of the "Kantian cut," considering

it "seriously and sympathetically, without adopting any

particular interpretation" can open up vistas. For one thing,

Madero's Spiritist Manual makes Mexico's 1910 Revolution

look glitteringly uncanny, like a prism ferried from the back

of a closet to a window. Or, shall we say, to an open door.

To return to Strieber and Kripal's The Super Natural, writes

Kripal: "History is not what we think it is."

Writes Strieber: "[T]his world is not what it seems, and

we do not know what it is, only that we are in it... I am reporting

perceptions, and what that means."

Was Madero really communicating with spirits of the dead? Well,

that's one hypothesis.

Many people know Strieber as "that guy who wrote about being

abducted by extraterrestrials." In fact, Strieber reports

his perceptions of his experiences, but as to what they actually

are, he says, "I am a wanderer, lost in a forest of hypotheses."

Strieber also echoes Kripal in arguing that, "it is not

necessary to believe in such things as flying saucers, aliens,

ghosts, and other unexplained phenomena in order to study them."

But to study such things without puckerlips, and all brain cells

firing, one must make that Kantian cut—and one needs courage

to persist, for that Kantian cut must be made again and again

in the face of our inclination towards easy polarities, to either

believe or, more commonly, reject, bristling with hostility or

scornful laughter.

As Kripal puts it, one must "learn to live with paradox,

to sit with the question."

But again, this sitting in the gray zone of maybes, this repeated

Kantian cutting—it becomes a kind of mowing—takes nerve,

both intellectual and social. It can prove hellishly uncomfortable.

Elegantly written and engaging as it is, it takes nerve to read

The Super Natural—not to mention Strieber's Communion.

However, in my experience of reading for my book about Madero's

book, it gets easier. So much ectoplasm, so many floating trumpets,

fairies and tulpas, psychic surgery... ho hum! It seemed I could

tackle anything, whether a purported download from the Akashic

records of Jiddu

Kirshnamurti's incarnations wending back to 22,662 B.C. (C.W.

Leadbeater's Lives of Alcyone, inscribed by its Spanish

translator to Mrs. Madero), Joan of Arc's autobiography (as channelled

by medium Léon Denis, one of Madero's favorite authors)

or, for instance, a modern parapsychologist's story about a sociopathic

psychic named Ted Owens and his hyperdimensional rain-making

confreres "Twitter" and "Tweeter" (Jeffrey

Mishlove's The

P.K. Man, which I picked up for late 20th century context).

Speaking of

Jeffrey Mishlove's The P.K. Man, I am not sure I could

have appreciated Kripal and Strieber's The Super Natural so

much as I do without having read that first. On its face, like

Strieber's Communion, or Madero's Spiritist Manual,

The P.K. Man would no doubt strike most readers as outrageous,

indigestible bizarrerie. Yet having read The P.K. Man

twice now, I concur with Harvard University Medical School Professor

John W. Mack, who writes in that book's forward, "Mishlove's

powerful true story may greatly help to clear the way for new

creative human visions and achievements." Speaking of

Jeffrey Mishlove's The P.K. Man, I am not sure I could

have appreciated Kripal and Strieber's The Super Natural so

much as I do without having read that first. On its face, like

Strieber's Communion, or Madero's Spiritist Manual,

The P.K. Man would no doubt strike most readers as outrageous,

indigestible bizarrerie. Yet having read The P.K. Man

twice now, I concur with Harvard University Medical School Professor

John W. Mack, who writes in that book's forward, "Mishlove's

powerful true story may greatly help to clear the way for new

creative human visions and achievements."

Mishlove concludes his story of mind over matter: "We must

move toward honest, authentic integration of the depths within

us and the facts before us." He holds the flag high. Yet

Mishlove confesses, it took him more than two decades to summon

the courage to publish The P.K. Man.

I myself procrastinated mightily in translating and writing about

Madero's Spiritist Manual. And I had assumed that I was

at the end of that years'-long road, with my  book

and the translation edited, formatted, and an index prepared,

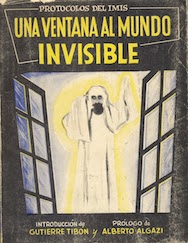

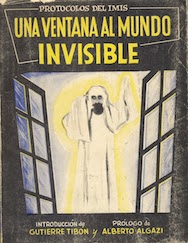

when in an antiquarian bookstore in Mexico City, I chanced upon

Una

ventana al mundo invisible (A Window onto the Invisible

World). Published in 1960, this exceptionally rare book contains

the detailed records of séances performed by ex-President

Plutarco Elías Calles, other prominent Mexicans, and a

medium named Luís Martínez, from 1940 to 1952 for

the Instituto Mexicano de Investigaciones Síquicas (IMIS).

Its dust jacket features a "spirit photograph" of "Master

Amajur," a 10th century astronomer who had much to say and

many a rose petal to materialize in many a dark night's séance.

After dipping into those spooky accounts, I could not sleep,

and my manuscript and galleys, which needed to be modified in

light of that book, sat untouched on a shelf for more than a

month. book

and the translation edited, formatted, and an index prepared,

when in an antiquarian bookstore in Mexico City, I chanced upon

Una

ventana al mundo invisible (A Window onto the Invisible

World). Published in 1960, this exceptionally rare book contains

the detailed records of séances performed by ex-President

Plutarco Elías Calles, other prominent Mexicans, and a

medium named Luís Martínez, from 1940 to 1952 for

the Instituto Mexicano de Investigaciones Síquicas (IMIS).

Its dust jacket features a "spirit photograph" of "Master

Amajur," a 10th century astronomer who had much to say and

many a rose petal to materialize in many a dark night's séance.

After dipping into those spooky accounts, I could not sleep,

and my manuscript and galleys, which needed to be modified in

light of that book, sat untouched on a shelf for more than a

month.

The first sentence Kripal writes in his own first chapter of

The Super Natural is, "I am afraid of this book."

When we make the Kantian cut, we can consider stories that might

seem not only ludicrous, but frightening—perchance beyond

frightening. Beyond one's world view by a galaxy.

For instance: As Strieber writes in The Super Natural,

after publishing Communion, he started receiving letters

from readers, "at first by the hundreds, then the thousands,

then a great cataract of letters, easily ten thousand a month,

from all over the world." They too had seen the haunting

face on the cover of Communion. Writes Strieber, "I

was deeply moved, not to say shocked, to see that I had uncovered

a human experience of vast size that was completely hidden."

And for instance: that Kripal himself, while in Calcutta during

the Kali Puja festivities, experienced an explosive out of- and

in-body state that he believes resonanted with some of Strieber's—and

thousands of others who gave similar testimony. And: Kripal finds

striking correspondences between American UFO abduction literature

and—who'dathunk?—Indian Tantric traditions.

And, finally, for instance: As his library and voluminous correspondence

attest, Francisco I. Madero did not come up with his ideas by

his lonesome; Spiritist Manual is not evidence of schizophrenia,

but a unique synthesis of what was in his time in the West the

cutting edge of a well-established literature of Spiritist /

Spiritualist, Buddhist, Catholic, Hindu, and occult philosophies.

But if, as Kripal and Strieber, Mishlove, and Madero all suggest,

we seriously consider these stories of anomalous phenomena—communication

with disembodied consciousnesses, out-of-body travel, psychokinesis,

telepathy, "the visitors," and so on and so forth,

how do we live our lives with dignity while entertaining the

notion that, say, someone, anyone, might read our thoughts, game

the financial markets, or, say, impel a pilot, of a sudden, to

crash his plane? And how do we avoid sinking into primitive credulities,

viscious paranoias, and, ultimately, barbarities such as the

burning alive of witches?

I think I mentioned, it can get uncomfortable.

Kripal writes, "many of the things that we are constantly

told are impossible are in fact not only possible but also the

whispered secrets of what we are, where we are, and why we are

here." But neither are Kripal and Strieber saying, believe

this or believe that. On the contrary; Kripal says, make that

cut. "Do not believe what you believe."

But whatever you believe, or not, that is a story. And stories

are what make us human. And being human— for that matter,

being able to read and write books, and so catch and hurl packages

of thought from across one axis of time and space to multiple

others— is both super and natural. As Kripal and Strieber

insist: super natural.

|

Book Review

by C.M. Mayo

Book Review

by C.M. Mayo by Whitley

Strieber and Jeffrey J. Kripal

by Whitley

Strieber and Jeffrey J. Kripal