|

Author of The Last Prince of the Mexican Empire, etc. |

|

|

|

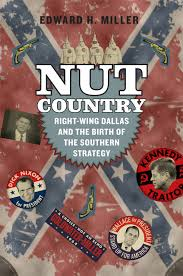

Attacking them as “the black man’s party,” these Democrats called for racial solidarity among whites and for rolling back the rights of African-Americans. For decades to come, Jim Crow Texas, like the rest of the South, was controlled by the so-called “yellow dog Democrats,” Democrats who would vote for their party’s candidate, even if he were a yellow dog. Yet by the 1960s, the Republican Party, now espousing conservatism, came roaring back in the Lone Star State. What happened? In the South of the 1960s, so the story goes, fiscal conservatives and segregationists were ill-at-ease and even outraged by the policies of liberal Democrats such as President John F. Kennedy and his successor, Lyndon B. Johnson. The Republican Party’s “Southern Strategy” was to coax those demoralized voters into its fold with an appeal to “states’ rights, lower taxes and less government regulation.” In Nut Country, Edward H. Miller argues that this process began sooner, in the mid-1950s; not in the South, but the Southwest; that “it was in fact explicitly racial in motivation and application”; that the role of Dallas, a wealthy and growing city at the crossroads between South, West, and North, with “a powerful local conservative movement,” was particularly significant; and that Dallas’ ultraconservatives played a more essential role in the Republican Party’s rise than has been previously recognized. The book’s title is taken from President Kennedy’s remark to his wife on the morning of his assassination in Dallas: “We’re heading into nut country today.” It is a tactless choice of title, as is its grab-‘em-by-the-collar opening line: “President Kennedy’s exploded head was a mark of the beast, some said, even during Kennedy’s televised state funeral throughout the long, gray weekend of November 23 to 25, 1963.” That some Americans entertain ideas bizarre and horrible to others — shall we say, to those of us who would write or read a book of political history published by the University of Chicago Press — is hardly news. For the record, I was at the University of Chicago, in the cafeteria in Reynold’s Club, on the day President Ronald Reagan was shot, and several of the workers there, otherwise unremarkable denizens of the South Side, were watching the TV with glee, openly wishing he would die. What I mean to say is, however repugnant others’ ideas may seem, to so flippantly label them “nuts” makes their power and origins more, rather than less, opaque. This is my one quibble with this solidly researched, well-argued, and illuminating work. Among a parade of others, Miller introduces H.L. Hunt, the richest man in the world, whose Facts Forum conflated liberalism with Communism and relished ferreting out Communist conspiracies; Ted Dealey, owner of the Dallas Morning News; John Bircher Gen. Edwin Walker; W.A. Criswell, pastor of the First Baptist Church of Dallas; and Bruce Alger, who was in 1954 elected the first Republican congressman from Dallas since Reconstruction, and who famously protested in the Adolphus Hotel against Lyndon Johnson — then JFK’s running mate — by pumping a placard that read, “LBJ SOLD OUT TO YANKEE SOCIALISTS.” Despite its title, Nut Country is not only about Dallas’ ultraconservatives: Miller also considers the moderate conservatives in the Republican Party and delineates, episode by episode, how their positions on various issues were molded by their reactions against or alliances with ultraconservatives, on the whole, tilting further right. By the 1950s, Dallas had a white-collar economy based on oil, aerospace, and financial industries. Its moderate conservatives, already members of (or ripe for the picking by) the Republican Party, included bankers, doctors, lawyers, and businessmen, and, as elsewhere in the United States, a vocal activist contingent influenced by philosopher Ayn Rand and economists such as Friedrich Hayek, championing small government, personal freedom (though not necessarily civil rights), and laissez-faire economics. The city’s Southern traditionalist conservatism and Protestant evangelical heritage combined — sometimes easily, other times awkwardly — with the more pragmatic conservatism of immigrants from the Midwest. Many of the latter had “grand expectations for the future and good reason for optimism.” Ultraconservatives, however, braced for cataclysm. Like their Maecenas, H.L. Hunt, many were premillennial dispensationalists; that is, they believed in the literal interpretation of the Bible’s Book of Revelation. They felt they were living in the end times, that the Antichrist would soon appear, or had already (some said he was Kennedy, others the Soviet Union or United Nations; certainly, there was no dearth of candidates), and this would signal the return of Jesus and the rapture, when He would raise the faithful to Heaven, leaving the rest of humanity to suffer the tribulation and the Apocalypse — the complete, final destruction of the world. For the premillennial dispensationalists, you either believed or you didn’t; you were either saved or lost; you were either with Jesus or with Satan. This binary thinking, coupled with the thrilling conviction that, as Miller puts it, “Satan’s war against Christianity was history’s biggest and most long-standing conspiracy,” translated directly into secular matters — and a preoccupation with conspiracy theories about everything from Communist agents in the White House to the nefarious purposes behind adding fluoride to the water supply. Whether in disgust or with a

chuckle, it would be easy for most academics and the reasonably

well-educated to dismiss the ultraconservatives’ ideas.

In recent times, these include the Birthers’ claim that

President Barack Obama was born in Africa. For scholars, the

difficult but fascinating task is to dig down to the roots of

such ideas and movements, evaluate their size and form, and identify

what, precisely, nourishes them. Toward this end, Nut Country

is a Texas-sized achievement. |