|

Lady of the

Seas Lady of the

Seas

By Agustín Cadena

Translated

by C.M. Mayo

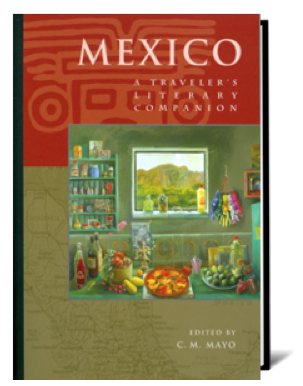

From Mexico:

A Traveler's Literary Companion

HER NAME

was Cielo, which means

"sky," and she lived in one of those Baja California

towns that, by the end of the 1960s, it seemed the whole world

was passing through. If at first it helped kill time, she soon

lost count of all the cars, motorcycles, and long-haired gringos

who stopped to fill-up on gas or to buy something, and then head

on south. They were all going to the Sierra Madre, or even further

south, to the Oaxacan coast. Seated on hand-made Hopi-Kachina

cushions, they would drink coffee or booze and talk about Ezra

Pound and the communitarian nature of artistic creation. For

them, poetry was a tribal bonfire and the poet should return

to recite his cantos in the plaza. They would go on about this

while watching the seagulls fly, and then they would leave. None

stayed for more than a couple of days, even with Señora

Gómez's cooking, and the charms of the plump-cheeked and

dark-eyed girls who waited on them in the restaurant. The heat,

the flies, and the town's lethargy drove them away. Year after

year, summer after summer, the sun parched the grass at the edge

of the highway that overlooked the ocean. And year after year,

Cielo had only Sundays to rest from the shrill ring of the cash

register in the little grocery where she worked. On Sundays she

went to mass in her barrio's church where she sang in the choir,

and afterwards, she would go to look at the ocean. She would

walk barefoot for a while along the beach, feeling that this

cold moistness on her feet was her portion of happiness for the

week, and when the sun went down and the mosquitos began to bite

her arms and calves, she would put on her shoes and head home

to get ready for the next week.

It was in the church choir that Cielo met Tacia. Although Tacia

was a few years younger, Cielo liked her at once, for she loved

animals, she was obsessed with leaning new things, and had a

spontaneous and natural tendency to contemplation, but most of

all, it was her way of laughing like a country girl, covering

her mouth as if she was ashamed to show her teeth or to let anyone

hear her.

As Cielo remembered it, the morning had been filled with sun.

It was one of the first sunny mornings of the year, a day so

festive that many of the hippies who were heading south took

off almost all their clothes and went to throw themselves on

the sand. From the hill where the church was, she could see the

dark sand sprinkled with bright bodies braided together in endless

kisses. At times, when the breeze from the sea changed direction

and blew towards the hill, she could hear singing and the muted

twang of a guitar.

"Wouldn't you like to go with them?" Tacia asked her

in a voice soft so that no one else would hear. Cielo just crossed

her arms. Tacia began to laugh in that funny way of hers, and

she moved away, towards the highway. Cielo followed.

"Are you going to the town?"

"Yes. You, too?"

And they walked along the highway, without looking at the beach.

For several months, they went on meeting on Sundays at church.

Soon they knew every small detail of each others's lives. Cielo

lived with her sister in the oldest part of town, next to an

enormous flour mill that hadn't worked in several decades. But

her sister was rarely home; all day she worked in a packing plant

and at night she just came in to change to her clothes and go

back out. Tacia, however, still had both of her parents. She

lived with them and two sisters and her grandfather, who was

paralyzed. Up until this time, Tacia's inner world had been nourished

by his stories about Pancho Villa. The old veteran would relive

his memories of the Revolution, when he fought by the general's

side all along the border, and Tacia was much happier to listen

to him than sit with her sisters watching the television that

never got good reception. Because of her grandfather, she got

the idea she wanted to become a nurse— even though her family

did not have the money or didn't want to pay for her studies.

In any event, she took advantage of every opportunity to follow

her vocation, about which she was learning more each time. Cielo,

however, had no ambitions for herself, but she admired her friend

and wanted to help her achieve her dreams. There was still time.

Tacia had only just graduated from junior high.

One day since morning Cielo felt dizzy and she had shivers. By

the time she closed up the grocery, she had a fever. Her sister

had gone to party in San Diego, but Tacia was with her. Defying

her parents, Tacia went to take care of her sick friend. She

stayed up with Cielo all night, spoon-feeding her medicines and

watching over her sleep until her back hurt from sitting up so

long in the bed. Two days later, Cielo was able to get up again,

feeling that her sickness was no more than a memory that was

actually a pleasant one, for it was lit with the glow of affection,

by smiles and words whispered in her ears by a voice full of

concern and hope.

It so happened that it was nearly mid-day when she opened her

eyes and saw how the June light came in only timidly through

the closed window of her sickroom. She felt that she longed for

air smelling of rain; she got up to open the blinds. Then she

got dressed and went out to the street. They were not expecting

her at the store yet, so she went for a stroll toward the highway

and then down the slope that was covered with wet grass. Waiting

stranded on the beach was the only friend she had had until Tacia

appeared: an old iron boat, its hull riddled with holes and completely

rusted. Many times Cielo had come here to gaze upon it and tell

it her secrets. At the end of the afternoon, a few seagulls arrived

to roost on the mast. Cielo heard them fighting and screeching

for the best perch; she heard the slap of the tide that had begun

to rise and she thought of Tacia, of her dark eyes filled with

tenderness, and she felt that she would have liked in this moment

to stop time.

She stayed there sitting on the sand for a long time, until the

sun was a red line on the other side of the sea and suddenly,

over the sound of the surf, she heard someone calling to her.

It was Tacia, who had come looking for her, worried because she

had not found her at home.

Cielo said nothing; she stood and held out her arms, which were

still weak.

Night surprised them there on the edge of the highway, innocently

hugging each other, each protecting the other, and each noticing

how the ocean, far in the distance, had begun to reflect the

glittering darkness. The earth gave off a strong and sensual

perfume.

Many times they hugged each other like this, their tenderness

immense and cowardly, each inhaling the scent of the other, incapable

of confessing what they felt. Maybe this was their way of protecting

that feeling. Because love, while called friendship, can last

indefinitely; it survives an earthquake thanks to one of most

perverse kinds of hypocrisy. But when it recognizes itself for

what it is, when love is called love, then, like Medusa, it turns

to stone. A stone statue that soon breaks apart and crumbles.

Yes. This is why they never spoke of it: they were afraid that

their love would come to an end. And they were embarrassed and

confused.

A few kilometers away, young people talked about free love and

the girls went braless and would make love twenty or thirty times

a day. But Cielo and Tacia were confused, and so they suffered.

Cielo was the older of the two and she felt responsible. She

was the one who would have to put some distance between them.

She started out by saying she was really busy, making up problems

her sister supposedly had, and that affected her as well. But

she could not stop what had begun. One Sunday after mass, Tacia

asked to come with her for a walk along the beach, and she brought

her to where there was an abandoned ship. She demanded an explanation,

and she began to cry. Cielo took her in her arms and she hugged

her with all her strength, and the power of this secret and lonely

love. She did not know what had happened.

September was mild in Baja California. The town awoke blanketed

in fog, but it was not cold. And the afternoons were brilliant,

golden. Someone on the beach lit up a reefer and began to recite

poems.

When you are in love, you feel wounded by the slightest things;

this is why it is easy to become ungrateful and cruel. Love is

also made of this.

One day, without saying goodbye, Tacia left. These were the last

years of Vietnam and the pressure of the hippies and pacifists

meant that there were ever fewer volunteers for the front. Many

Mexicans enlisted in the U.S. Army. Tacia offered her services

as a nurse. But Cielo did not find this out until many years

later, when the war was over and she saw her friend's name on

a list of casualties. She had waited for her for so long... She

had waited for her on the beach, in church, in the grocery, every

day, every afternoon. Even among the groups of hippies who came

in to buy things, she would search for her face, her voice. Time

went by and with it that was of life. One day, a girl came into

the store. She was wearing a multicolored blouse and sandals

and she had flowers in her hair and flowers painted on her cheeks.

She bought some tomatoes and a pen, because she said, she was

going to write a sonnet. When she left, a speeding car ran her

down. She was already dead when the ambulance took her away.

Cielo understood that this was the last of a race of young people

to whom, who knows how, her friend had belonged. And she felt

cold.

The following Sunday, on leaving church, an admirer offered her

his arm and she accepted it. She was nearly thirty years old

and she did not want to go on alone. They went to walk along

the highway and then down toward the beach. The iron boat was

still there, invincible, like a guardian. The man proposed that

they climb up onto it, and this surprised her. It had never occurred

to her to that it could be possible to clear this small stretch

of water and storm this kingdom of crabs and gulls. Nevertheless,

she did not want to; it seemed to her a kind of desecration.

The more her companion insisted, the more stubbornly she refused.

In the end, he contented himself by moving the boat a little

bit and with a pen-knife, scraping off the rust that covered

its name. But for Cielo, even this seemed to her an attack on

something that should not be touched. The name of the boat, like

hundreds of others in North America, was Lady of the Seas. Cielo

did not want to know it. When she turned her back to the beach

and started walking toward the highway, the only thing in her

mind was to forget the past. In the last memory she allowed herself

from that time, she saw herself lying naked on the grass, covering

her eyes with her arm and trying to catch her breath, while Tacia

looked at her and smiled, covering her mouth like a country girl.

Copyright

2004. All rights reserved. Translation originally published in

Terra Incognita.

.

>Back to TOC & Excerpts

>Agustín

Cadena

|